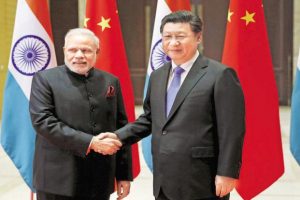

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the coastal Chinese city of Xiamen was important for several reasons. For one, this was the first time PM Modi and President Xi Jinping were meeting face-to-face since the standoff at Doklam, which saw an unprecedented sabre-ratting from the Chinese side. Scheduled ahead of the 19th Communist Party Congress, whose dates – beginning 18 October, 2017 – were announced just after the disengagement agreement, the 9th BRICS Summit – attended by the leaders of India, China, Russia, Brazil and South Africa – was showcased by Chinese President Xi Jinping as a platform for his global leadership. A combination of these circumstances, in addition to concerns expressed by the US and other powers, probably including Russia, the highly tense Korean peninsula and some quiet diplomacy by the Indian side led to the disengagement where the CBMs between the two armies firmly held, despite the jingoistic noises.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the coastal Chinese city of Xiamen was important for several reasons. For one, this was the first time PM Modi and President Xi Jinping were meeting face-to-face since the standoff at Doklam, which saw an unprecedented sabre-ratting from the Chinese side. Scheduled ahead of the 19th Communist Party Congress, whose dates – beginning 18 October, 2017 – were announced just after the disengagement agreement, the 9th BRICS Summit – attended by the leaders of India, China, Russia, Brazil and South Africa – was showcased by Chinese President Xi Jinping as a platform for his global leadership. A combination of these circumstances, in addition to concerns expressed by the US and other powers, probably including Russia, the highly tense Korean peninsula and some quiet diplomacy by the Indian side led to the disengagement where the CBMs between the two armies firmly held, despite the jingoistic noises.

BRICS-plus: China’s global ambitions

The 9th BRICS summit, taking place a few months after another image-building extravaganza – the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) summit in May – became the occasion for the Chinese proposal for ‘BRICS Plus’ for the forum’s expanded institutionalised international role. As distinct from the outreach BRICS summits witnessed in Goa and earlier, this engagement was ostensibly for “an open and diversified network of development partnerships to get more emerging markets and developing countries involved,” as expressed by President Xi. Simply put, both these forums are envisaged by the Chinese leader to create a parallel international structure as the ‘established’ multilateral institutions feel the negative impact of President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ policy.

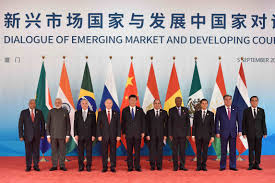

The summit was attended by the five members at the heads of state/government level on September 4 which was followed the next day by five other heads of state from Egypt, Mexico, Tajikistan, Guinea and Thailand joining them in a Dialogue of Emerging Markets and Developing Countries. In his plenary session speech to the BRICS partners, President Xi described the first decade of the organization “but a beginning” in cooperation amongst the members and declared the second “golden decade” as entailing result-oriented economic cooperation, complementarities of development strategies, joint “solution” to international peace and development, commitment to multilateralism and basic norms governing international relations and people-to-people contacts. Prime Minister Modi in his plenary remarks stated that BRICS contributes “stability and growth in a world drifting towards uncertainty.” The Indian foreign office briefing mentioned Mr Modi’s remarks at the restricted session being directed at missed opportunities for UNSC reforms, counter-terrorism and disaster relief. The intent was obvious, given intra-BRICS divergent opinions on these critical matters.

The summit was attended by the five members at the heads of state/government level on September 4 which was followed the next day by five other heads of state from Egypt, Mexico, Tajikistan, Guinea and Thailand joining them in a Dialogue of Emerging Markets and Developing Countries. In his plenary session speech to the BRICS partners, President Xi described the first decade of the organization “but a beginning” in cooperation amongst the members and declared the second “golden decade” as entailing result-oriented economic cooperation, complementarities of development strategies, joint “solution” to international peace and development, commitment to multilateralism and basic norms governing international relations and people-to-people contacts. Prime Minister Modi in his plenary remarks stated that BRICS contributes “stability and growth in a world drifting towards uncertainty.” The Indian foreign office briefing mentioned Mr Modi’s remarks at the restricted session being directed at missed opportunities for UNSC reforms, counter-terrorism and disaster relief. The intent was obvious, given intra-BRICS divergent opinions on these critical matters.

The Xiamen BRICS Declaration, issued by the five leaders, covers a vast gamut of issues of mutual economic cooperation, global economic governance and peace and security to address the organisation’s objectives of a fairer global political and economic order. On the economic side, the document makes no mention of China’s flagship BRI programme due to, perhaps, Indian reservations. On the political side, the formulations on key international issues, including the Korean crisis, do not fall four square within the US positions on them.

On the UN Security Council aspirations of the three member countries, namely India, Brazil and South Africa, the other two countries, currently permanent UNSC members, have not consistently yielded any ground in support.

Terror Connect?

Although regarded as a major diplomatic success for India, the language of the declaration on counter-terrorism is quite nuanced since it mentions “violence caused” by specific named groups which are not called terrorists, but which are embedded in a strong language on cooperation against terrorism in general.

Even though a Chinese diplomat told a Pakistani journalist that this language was lifted from the Heart of Asia Conference Declaration 2016 held in Amritsar, with which Pakistan had agreed “to some extent”, nerves were frayed in Pakistani establishment coming as it did soon after President Trump’s scathing comments against the country in his policy statement on South Asia. It has reignited within the establishment the internal divisions about home-based terrorist groups which were in evidence following the Indian Army’s surgical strikes in September last year.

It is still early days as to whether this formulation on counter-terrorism will have any concrete outcome to address Indian concerns about the destabilising role of Pakistani terrorist groups. Although specific achievements were listed by the Indian spokesperson, including the BRICS Bank (New Development Bank) and the CRA (Contingent Reserve Arrangement for currency swaps), it is worth recalling that most of the member countries’ economies are not doing well, which makes coordination for maximising their international influence less impactful. Goldman Sachs, which coined the acronym BRIC (2001), has closed down its BRICS Investment Fund after years of losses. There is also an inadequate convergence of strategic interests amongst the five member countries; India and China nearly went to war on the eve of the summit.

The summit meeting of the BRICS leaders and the selected Emerging Market and Developing Economies countries on September 5 witnessed President Xi speaking about building “extensive development partnerships” for South-South cooperation and offering $ 500 million in assistance. At this forum, he spoke at length about the BRI programme calling it “as much a path of cooperation as one of hope and mutual benefit.” Prime Minister Modi spoke in more general terms about South-South cooperation. It remains unclear as to how the new BRICS mechanism would fare under the incoming South African and subsequent presidencies.

Modi-Xi meeting: The Way Ahead

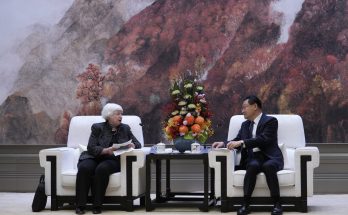

Apart from Modi’s other meetings at Xiamen, the most talked about was the one with Xi. In an apparent reference to the Doklam episode, India’s Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar stated in his briefing that both sides decided to open a new “forward-looking” round of engagement anchored by fresh mechanism for CBMs since “peace and security in the border areas was a prerequisite for further development of the bilateral relationship and there should be more effort to enhance and strengthen the level of trust between the two sides.” He described the two leaders as laying out “a very positive” view of the relationship. The Chinese official readout on this meeting was a little downbeat. According to the Chinese side, President Xi talked about “broad consensus on developing China-India relations” between the leaderships on both sides, stressing its commitment to the Five Principles (Panchsheel) to “move forward… relations on the right track” and that the two sides’ endeavour to make “the international order just and equitable”; the last one is aimed at India’s growing proximity towards the US. There have also been media reports, attributed to official sources, that both sides have not yet fully withdrawn from the standoff site in Doklam.

Apart from Modi’s other meetings at Xiamen, the most talked about was the one with Xi. In an apparent reference to the Doklam episode, India’s Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar stated in his briefing that both sides decided to open a new “forward-looking” round of engagement anchored by fresh mechanism for CBMs since “peace and security in the border areas was a prerequisite for further development of the bilateral relationship and there should be more effort to enhance and strengthen the level of trust between the two sides.” He described the two leaders as laying out “a very positive” view of the relationship. The Chinese official readout on this meeting was a little downbeat. According to the Chinese side, President Xi talked about “broad consensus on developing China-India relations” between the leaderships on both sides, stressing its commitment to the Five Principles (Panchsheel) to “move forward… relations on the right track” and that the two sides’ endeavour to make “the international order just and equitable”; the last one is aimed at India’s growing proximity towards the US. There have also been media reports, attributed to official sources, that both sides have not yet fully withdrawn from the standoff site in Doklam.

The impact of the two leaders’ meeting on India-China relations, which have deteriorated in recent times, still remains to be seen. The Doklam episode brings out the linkage between the border tension and the Chinese perception of India joining the US in “containing” it. These relate to divergent – and potentially conflicting – perspectives of the two countries about each other’s policies in South Asia, the Indian Ocean and the wider Indo-Pacific region where the existing, or proposed, dialogue processes would need to clear their respective minds about the intentions of the other. On the eve of the Chinese Communist Party Congress, the Chinese leader’s sensitivity about his projection as a global leader, with the new US president becoming less globally engaged, remains a significant domestic political factor. The post-October emergent shape of the Chinese leadership would make considerable difference as to how stable global situation would be where India’s vital interests – and its multi-vector international relationships – remain at stake.

(Yogendra Kumar is the author of Diplomatic Dimension of Maritime Challenges for India in the 21st Century. A former diplomat, he had served as Ambassador of India to the Philippines and held important postings in key capitals. The views expressed in this column are solely those of the author)

(Yogendra Kumar is the author of Diplomatic Dimension of Maritime Challenges for India in the 21st Century. A former diplomat, he had served as Ambassador of India to the Philippines and held important postings in key capitals. The views expressed in this column are solely those of the author)

Author Profile

- India Writes Network (www.indiawrites.org) is an emerging think tank and a media-publishing company focused on international affairs & the India Story. Centre for Global India Insights is the research arm of India Writes Network. To subscribe to India and the World, write to editor@indiawrites.org. A venture of TGII Media Private Limited, a leading media, publishing and consultancy company, IWN has carved a niche for balanced and exhaustive reporting and analysis of international affairs. Eminent personalities, politicians, diplomats, authors, strategy gurus and news-makers have contributed to India Writes Network, as also “India and the World,” a magazine focused on global affairs.

Latest entries

In ConversationJuly 26, 2024India-Italy defence collaboration can extend to third countries: Anil Wadhwa

In ConversationJuly 26, 2024India-Italy defence collaboration can extend to third countries: Anil Wadhwa In ConversationJuly 23, 2024Italy views India as a key partner in Indo-Pacific: Vani Rao

In ConversationJuly 23, 2024Italy views India as a key partner in Indo-Pacific: Vani Rao DiplomacyJune 29, 2024First BRICS unveils a roadmap for boosting tourism among emerging economies

DiplomacyJune 29, 2024First BRICS unveils a roadmap for boosting tourism among emerging economies India and the WorldJune 11, 2024On Day 1, Jaishankar focuses on resolving standoff with China

India and the WorldJune 11, 2024On Day 1, Jaishankar focuses on resolving standoff with China