The presence of strong leaders like Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi opens up the possibilities of path-breaking initiatives that could benefit both countries and transform the geo-political landscape in the region. Given China’s military and economic strength and assertive territorial claims, it will be up to Beijing to initiate the first steps, says Jayadeva Ranade

The presence of strong leaders like Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi opens up the possibilities of path-breaking initiatives that could benefit both countries and transform the geo-political landscape in the region. Given China’s military and economic strength and assertive territorial claims, it will be up to Beijing to initiate the first steps, says Jayadeva Ranade

India-China relations are presently at a critical stage. The decisions and events of the next 2-5 years will be crucial and could mark a new phase in the relationship. At the same time the flux in geostrategic alignments in the world, caused by the potential shift in the global balance of power to the East, have got accentuated with the election in November 2016 of Donald Trump as the 45th US President and consequent uncertainty about his policies.

Strong Leaders, Tough Choices

The almost simultaneous emergence of strong, new leaders, namely Xi Jinping in China, Narendra Modi in India and Shinzo Abe in Japan, has injected an element of competition in the region. All three are pragmatic leaders with a track record of being decisive and a capacity to take bold decisions. Each has articulated an ambitious vision for his country and all are strongly nationalist. Economic development is the centrepiece of the plans of each of these leaders, but they are equally intent on securing their strategic space and national interests. All of them began to outline the strategic perimeters of their national interests soon after assuming office. Their appearance on the international stage has the potential to crowd the Indo–Pacific region or boost its economy.

China, which will define the backdrop for the region’s political dynamics during the next 5-10 years, has itself transformed into a major economic and military power following more than three decades of extraordinary growth. It has, since the end of 2007, discarded Deng Xiaoping’s dictum of “lie low, bide your time” and adopted a set of assertive policies. This was prompted by a combination of factors, but mainly by the global economic downturn; China’s considerably enhanced economic and military strength; and Beijing’s perception that the US as a global power is temporarily on the decline and that the next few years offer the opportune moment for China to regain its self-perceived rightful position on the world stage and alter the status quo in Asia.

Separately, inside China arguments advocating a pro-active, tough and uncompromising approach are dominant in the debate on China’s international security environment. The views of prominent and influential Chinese strategists and academics close to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reflect this. Additionally, the increasingly vociferous ‘nationalist’ Chinese netizens have become a factor in discussions touching on issues of sovereignty or territory. Tsinghua University Professor Yan Xuetong, a former doctoral tutor of Xi Jinping with reportedly close proximity to him, recommended, among other things, that: (i) as the probability of conflict with other countries increases, China’s foreign policy should directly confront rather than avoid the issue of conflict; (ii) China should try to develop rather than just maintain its “strategic opportunity period” because waiting for a strategic opportunity period is always passive; and (iii) China should begin to shape rather than just integrate into international society because China now has the capacity to do so.

Xu Jin, another influential Chinese scholar of the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), called for debunking several dominant “myths” in Chinese foreign policy. Among the ‘myths’ he listed are: (i) China should keep a low profile; (ii) China should not seek alliances; (iii) China will not become a superpower; and (iv) China’s foreign policy should serve China’s economic development. He underlined that all these six “myths” should be discarded as a ‘new era’ calls for new ideas.

The China Dream

The 18th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in November 2012 ushered in a period of definite domestic change. In addition, China unveiled a muscular foreign policy reflective of the arguments advanced by Chinese strategists and endorsed the concept of the ‘China Dream’ articulated by Xi Jinping to the 18th Party Congress. The ‘China Dream’, which advocates the “rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation” and is a call to redress past humiliations and “recover lost territories”, is of direct relevance to India which has a 4057-km long disputed border with China. The Congress also dubbed China a maritime power, thereby asserting its goal of acquiring sovereignty over a large portion of the South China Sea and a presence in the Indian Ocean.

It also appointed Xi Jinping to China’s three top posts of General Secretary of the CCP, Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) and President of China at the same time – making him the first Chinese leader since Hua Guofeng (1976-78) to be so appointed. With the addition of the position of PLA Commander-in-Chief, he today holds more formal titles than any past leader of the CCP. He chairs more Central Small Leading Groups than previous CCP Chiefs and has also concentrated greater power exercising direct authority, including over China’s security, military, economic and foreign policy apparatus.

India soon began to feel the effect of the new policies. The two major incursions in India’s Ladakh sector in April 2013 and September 2014 both occurred after Xi Jinping took over. Each was deliberately timed, with the one in April taking place just days before the first visit to India of Li Keqiang as Premier, and that in September 2014 actually happening during, and continuing till after, Xi Jinping’s first visit to India as Chinese President and CMC Chairman. Within a month of the intrusion in April 2013, the influential ‘Zhongguo Qingnian Bao’ (China Youth Daily) on May 14, 2013 enlarged China’s territorial claims on India and reiterated a claim over Ladakh, which it said had been under Chinese rule since the time of the Yuan Dynasty and which shared the customs, religious practices and traditions of Tibet. The article said Ladakh has long been dubbed as “Little Tibet.” Considering that the same People’s Liberation Army (PLA) commanders were in position during both intrusions and the Lanzhou Military Region Commander, Liu Yuejun was promoted to the rank of full General in early 2015 and early this year appointed to head the PLA’s newly created East Zone Theatre Command, it is apparent that both intrusions were planned and approved at the highest levels and that General Liu Yuejun enjoyed the full confidence of the CMC Chairman. It has, additionally, been made clear in various high-level interactions after April 2015 that the Chinese leadership gives little importance to resolving the disputed Sino-Indian border which, for India, is a priority.

Friends & Enemies

As head of the Central Small Leading Foreign Affairs Group, Xi Jinping has guided China’s assertive policy on the South China Sea and directly oversees policies concerning India and other nations. The Conference on Peripheral Diplomacy, held in October 2013, gave a new orientation to China’s foreign policy and, for the first time in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), designated countries as “friend” or “enemy” and promised “friends” untold financial and other benefits including security alliances. It said those hostile to China, or opposed to it, will be confronted with sustained periods of tough sanctions and isolation. Soon thereafter, Xi Jinping announced the ‘One Belt, One Road’ strategic geo-economic initiative and in April 2015 ‘operationalised’ the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The latter has aroused considerable concern in India especially as it implies that Beijing has, dispelling decades of ambiguity, decided to accept de facto Pakistan’s claims on the status of Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK) and Gilgit and Baltistan, which are all Indian territories under Pakistan’s illegal occupation. The military content implicit in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor adds to the concern.

China-Pakistan Nexus

China’s enhanced relationship with its ‘ally’ and ‘only friend’ Pakistan has a real potential to sour India-China ties. Beijing’s endorsement of Pakistan’s claim seemingly became more definite when the CCP’s official newspaper ‘People’s Daily’ published a report on July 21, 2016, depicting soldiers from Pakistan and China under the caption: “A frontier defense regiment of the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) in Xinjiang, along with a border police force from Pakistan, carries out a joint patrol along the China-Pakistan border.” It is noteworthy that the area of the patrol, identified in the report as “the China-Pakistan border,” is the frontier region of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir — an area which is an integral part of India’s territory. China usually refers to the disputed area as “Pakistan-administered Kashmir”. China’s stance in reporting on developments relating to Kashmir has also become more critical.

Other visible recent instances of unfriendly Chinese actions are its blocking of Indian requests at the UN Sanctions Committee regarding international terrorists being harboured by Pakistan and China and Pakistan colluding to block India’s admission to the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and the UNSC. As evident from the statement by China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman in December 2016, there is negligible prospect of Beijing changing its position on either of these issues in the near future. The vetoing of India’s requests regarding the terrorists harboured by Pakistan at the UN Sanctions Committee suggests that Beijing does not object to Islamabad using terrorism as an instrument of policy against India.

The Modi Factor

There have been changes in India too, where the general elections in May 2014 brought to power a new BJP government with a mandate unprecedented in the last 30 years. The overwhelming mandate ensures that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is not hostage to considerations of state politics in crafting foreign policy and can take bold initiatives. Modi moved quickly and even as Prime Minister-designate initiated a phase of hectic diplomacy that sought to re-energise some important relationships and create room for manoeuvre. In the process he outlined the geographic perimeter of India’s neighbourhood of strategic interest and implicitly identified the areas where India and China’s national and strategic interests will bump against each other.

China tracked India’s general elections and, observing that Modi represents a right-wing political party, noted his utterances on the campaign trail and visit to Arunachal Pradesh. China’s official media and senior researchers in Chinese government think-tanks differed on whether India’s stand on China would harden in Modi’s tenure. China’s leadership began to woo India to prevent the new leadership from drawing closer to the US and Japan as well as to seize economic opportunities. Articles in China’s state-controlled media projected that India-China economic relations would improve. The authoritative official ‘Xinhua’ despatch of May 29, 2014, though, differed noticeably in tone from other Chinese media reports. It asserted that Modi has no option other than economic cooperation with China as India perforce has to recognise China’s economic and military superiority in Asia. It stressed that Modi would have to accommodate China, not out of choice or inclination, but out of necessity.

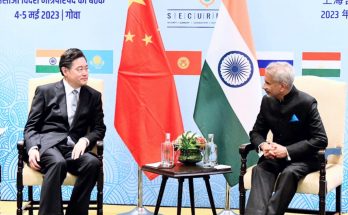

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited (June 8-9, 2014) India soon after Modi’s election to engage with India’s new right-wing ‘nationalist’ Government and assess its attitude towards China. Wang Yi emphasised that China’s focus is on economic cooperation, but on the crucial issue of resolving the border dispute indicated that China will not yield any ground. In a carefully worded remark at a press conference, he described the stapled visas being issued by China as a “unilateral”, “flexible”, “goodwill gesture” or, in other words, that the status of Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir remains disputed.

India nonetheless encouraged economic interaction and invited Chinese companies and investment. A number of Chinese companies are working profitably on projects in India. Telecom companies like Huawei and ZTE earned profits of around US$ 6 billion and US$ 200 million in 2015 alone. State governments in India are also interacting with Chinese business enterprises. Chinese direct investment in India has, however, been marginal. China’s sustained opposition to lifting arbitrary domestic restrictions on certain industries and products has prevented redressal of the huge adverse trade balance.

The Modi government is also uncompromising on issues concerning the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. This has been made clear by Prime Minister Modi raising the question of resolution of the disputed border as the first item on his agenda at each summit meeting with Xi Jinping. The greatest impediment to the India-China relationship achieving its full potential remains the boundary issue and this has been publicly stated by Modi in Beijing. The intrusion by Chinese PLA troops in September 2014 and on two other occasions in December 2015 and in mid-2016 all met with a firm Indian response with the face-offs stretching for days before Chinese troops backed off. India has neither restricted visits by Uyghen Thinley, widely regarded as the Gyalwa Karmapa, in November 2016 and the Dalai Lama to Arunachal Pradesh, scheduled for April 2017. India has additionally accelerated the build-up of its defence infrastructure and, with the final testing of the 5000-5500 kms range Agni-V ICBM, has acquired deterrent asymmetric capability.

The Way Ahead

Ties between India and China are, presently, marked by mutual suspicion. Chinese South Asia expert, Renmin University Professor Shi Yinhong, has said that “Vietnam, Myanmar and India are very significant in economic, geopolitical and geo-strategic senses, and the fact is that they (India in particular) harbour the strongest suspicions and vigilances regarding China”. The state of their ties with China is very poor and for China to promote the “Maritime Silk Road” and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar economic corridor, and handle the South China Sea issue as well as its territorial disputes with India, it must try to reduce their doubts and dissatisfaction. Adding that “tensions on China-Indian borders have resulted in increased suspicion and discontent”, he recommended that “China must come up with a sensible order of strategic priority for such concerns”. More recently, Hu Shisheng, Director of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, which is a think-tank of China’s Ministry of State Security, observed that it is alright if India keeps away from OBOR, “but China is concerned if India will do something to block it, then it is terrible.” Former PLA Navy (PLAN) Senior Captain Li Jie, presently a senior researcher at the Chinese Naval Research Institute in Beijing and reputedly an influential voice in China’s naval strategy development, in Military Digest pointed to India as a potential threat to China’s maritime trading routes. Such mutual suspicion will make the task of both countries improving their economic conditions and the people’s standards of living even more difficult.

Ties between India and China are, presently, marked by mutual suspicion. Chinese South Asia expert, Renmin University Professor Shi Yinhong, has said that “Vietnam, Myanmar and India are very significant in economic, geopolitical and geo-strategic senses, and the fact is that they (India in particular) harbour the strongest suspicions and vigilances regarding China”. The state of their ties with China is very poor and for China to promote the “Maritime Silk Road” and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar economic corridor, and handle the South China Sea issue as well as its territorial disputes with India, it must try to reduce their doubts and dissatisfaction. Adding that “tensions on China-Indian borders have resulted in increased suspicion and discontent”, he recommended that “China must come up with a sensible order of strategic priority for such concerns”. More recently, Hu Shisheng, Director of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, which is a think-tank of China’s Ministry of State Security, observed that it is alright if India keeps away from OBOR, “but China is concerned if India will do something to block it, then it is terrible.” Former PLA Navy (PLAN) Senior Captain Li Jie, presently a senior researcher at the Chinese Naval Research Institute in Beijing and reputedly an influential voice in China’s naval strategy development, in Military Digest pointed to India as a potential threat to China’s maritime trading routes. Such mutual suspicion will make the task of both countries improving their economic conditions and the people’s standards of living even more difficult.

The presence of strong leaders like Xi Jinping and Modi opens the possibility of bold tension-reducing initiatives that can create huge win-win opportunities, which will benefit both countries and alter the geo-political climate in the region. Given China’s military and economic strength and assertive territorial claims, it will be up to Beijing to initiate the first steps. Thus far, Xi Jinping has shown no sign of taking such an initiative.

India-China@2020: Projections & Trends

- Over the past year and a half, strains in India-China relations have increased. These appear unlikely to ease in the next few years. As China pushes ahead with its ambition of emerging as the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific, it becomes more important for it to nurture a friendly neighbourhood. China needs to realise that India and China are the two largest powers in Asia, and without India’s assistance China will not be able to achieve its goals.

- To lend stability to the relationship, it is essential that China begins by building trust, which is presently negligible. The first step towards this would be for China to be sensitive to India’s concerns on sovereignty, territorial integrity, and national security.

- India has no objection to China’s friendship with Pakistan, but China must ensure that it does not impinge on India’s security concerns as does China’s veto of India’s requests regarding internationally acknowledged Pakistan-based terrorists like Masood Azhar and Hafiz Sayeed.

- Transparency is required in China’s assistance to Pakistan in the nuclear field.

- China must stop all military intrusions along the border. Each intrusion, in a free democratic country like India, undermines whatever trust might have been built.

- China and India must both soon identify/nominate a military point of contact for defusing tension created by military intrusions and/or clarifying the situation. Failure to do so has meant prolonged confrontation on the border which is not desirable.

- The hotline between the military Hqs should, as agreed, be operationalised. This would be a meaningful confidence-building step.

- High-level visits by themselves do not build trust. They must be accompanied by an honest exchange of views, clarifying intent.

- Concrete investment in India, especially in infrastructure and long gestation projects, will help build confidence.

(Jayadeva Ranade is President of the Centre for China Analysis and Strategy and a well-known commentator on India-China relations)

(Jayadeva Ranade is President of the Centre for China Analysis and Strategy and a well-known commentator on India-China relations)

- This article was originally published in India and World, a magazine-journal focused on international relations, and published by India Writes Network/TGII Media Private Limited. To subscribe to India and World, write to editor@indiawrites.org)

Author Profile

- India Writes Network (www.indiawrites.org) is an emerging think tank and a media-publishing company focused on international affairs & the India Story. Centre for Global India Insights is the research arm of India Writes Network. To subscribe to India and the World, write to editor@indiawrites.org. A venture of TGII Media Private Limited, a leading media, publishing and consultancy company, IWN has carved a niche for balanced and exhaustive reporting and analysis of international affairs. Eminent personalities, politicians, diplomats, authors, strategy gurus and news-makers have contributed to India Writes Network, as also “India and the World,” a magazine focused on global affairs.

Latest entries

DiplomacyApril 23, 2024Resetting West Asia, re-booting the world, but not fast enough: T.S. Tirumurti

DiplomacyApril 23, 2024Resetting West Asia, re-booting the world, but not fast enough: T.S. Tirumurti India and the WorldApril 22, 2024India’s G20 Legacy: Mainstreaming Africa, Global South in global agenda

India and the WorldApril 22, 2024India’s G20 Legacy: Mainstreaming Africa, Global South in global agenda DiplomacyApril 10, 2024Diplomat-author Lakshmi Puri pitches for women power at LSR

DiplomacyApril 10, 2024Diplomat-author Lakshmi Puri pitches for women power at LSR India and the WorldApril 6, 2024UN envoy pitches to take India’s solutions to the world stage

India and the WorldApril 6, 2024UN envoy pitches to take India’s solutions to the world stage