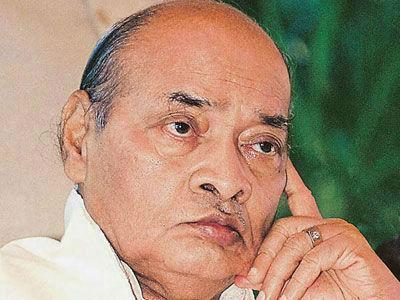

Who was the architect of India’s path-breaking economic reforms of 1991? No prize for guessing it? Think again, it’s time to get it right! It wasn’t Manmohan Singh, widely seen as the father of India’s economic liberalization, but one of the most underrated leaders of the country, Pamulaparti Venkata Narasimha Rao. In his book “1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Made History,” author and economist Sanjaya Baru has vividly brought out the role of PV, as he was popularly known, in leading the process of economic liberalization from the front by responding dynamically to the country’s balance of payments crisis and appointing Manmohan Singh as the finance minister. Narasimha Rao had many choices for the prized post of finance minister, including the redoubtable I.G. Patel, but finally he zeroed in on Manmohan Singh as he wanted an international economist to shepherd the economic reforms at that crucial juncture in 1991. Manmohan Singh was not only an accidental prime minister, but also an accidental finance minister, says the author.

In the end, it was a twist of history that Rao’s role in initiating economic reforms as in many other transformative processes in the country’s foreign policy remains undervalued and underappreciated to this day.

In this wide-ranging conversation with Manish Chand, Editor-in-Chief of India Writes Network, Dr Baru, a former media advisor to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and a veteran journalist, speaks about defining events of 1991, the pivotal year in not just India’s economic journey, but also in the country’s politics and foreign policy, and the crucial role of Narasimha Rao in shaping outcomes conducive to India’s national interests. In the realm of foreign policy, Dr Baru outlines defining steps taken by Narasimha Rao in response to emerging global power shifts, including the launch of Look East policy, resetting relations with the US and China and the outreach to Israel. Commenting on the ongoing political churn in India, the author says that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2004 election victory has brought a quarter century of accidental prime ministers in the country to an end, but he needs a second term to leave a lasting legacy.

(Excerpts from the interview)

1991: The Turning Point

Q) What provoked you to zero in on 1991 as the overarching theme of your book? 1991 was clearly a defining year in India’s politics as well as in the global geopolitical landscape. What exactly was the thought process that led you on to write this book?

A) The most important reason was that I found very few young people today are aware of Narasimha Rao’s contribution and, in many of my interactions, in universities I go to and lecture to young people in different parts of the country, I found that when you ask the question what happened in 1991, what do you think the political leadership did at that time, very few people knew the answer — the maximum they could say was that India had economic liberalization and Manmohan Singh was responsible for it. I felt the need to write a book making people aware of the role of the Prime Minister of the day: Mr. P.V. Narasimha Rao. But when I started thinking about the book, I realised that 1991 was not just about economic liberalization, it was more than that. It was year of the end of the Cold War, it was also the year in which the Nehru–Gandhi family’s 30-year-old reign under Nehru, Indira and Rajiv that had come to an end. So in that sense 1991 was the turning point not just for the economy, but also for the India foreign policy and for the India politics. So what began as a book on Narasimha Rao actually ended as a book on the year 1991; which is why title of the book is also “1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao made history.

Q) Coming back to popular mythology, Manmohan Singh is widely seen as the architect of economic reforms. As you have rightly said in the book, without Narasimha Rao’s political will this could not have happened. How much of the credit for economic reforms goes to Narasimha Rao or Rao and Manmohan Singh acted in tandem?

A) First of all, many of us in the media, particularly in business media, are as guilty as the members of the Congress party for having erased the legacy of Narasimha Rao over the last 25 years. Not only the Congress party and media in general, but the financial media in particular repeatedly referred to Manmohan Singh’s role or Montek Singh Ahluwalia‘s role or P. Chidambaram’s role but ignored Narasimha Rao’s role. And therefore I felt it necessary to underline Narasimha Rao’s role. Now come to the facts: the fact is is that the day Narasimha Rao became the Prime Minister, when cabinet secretary Naresh Chandra apprised him of the economic situation Narasimha Rao’s instinct was to first ask for I.G. Patel as the finance minister. In other words, he recognized the need to bring in a professional economist, it is he who took the decision that the finance minister should be someone with international reputation and international credibility; so in that sense he was the originator of the political approach to the economic change. When I.G. Patel declined and said for his personal reasons he didn’t want to become the finance minister, then Narasimha Rao approached Manmohan Singh. So Manmohan Singh’s role in that period happened because the prime minister of the day decided to invite him to become the finance minister; that is the sequence of events we have to recognize, that the initiative was taken by Narasimha Rao.

Two people were hoping to become the finance Minister at that time – both Pranab Mukherjee and Chidambaram were thinking that they could become the finance minister, but Narasimha Rao choose Manmohan Singh because he wanted an economist with international standing, which is exactly what he told a lot of people around him and I have quoted that in my book. So I would say that the process of change was led by Narasimha Rao and the implementation was done by Manmohan Singh

Q) So it was an accidental thing, a twist of history that Manmohan Singh came to be associated with the path-breaking economic reforms of 1991. Just as Manmohan Singh was the accidental prime minister, as you wrote in another book of yours, are you suggesting that he was also the accidental finance minister?

A) Yes, he was the accidental finance minister. Because if I.G. Patel had said yes to Narasimha Rao, he would have been the finance minister.

Q) Do you use this phrase accidental finance minister in your book?

A) No, I didn’t use the term accidental finance minister. It was Narasimha Rao‘s vision that the country needed this kind of change and for which mandate he appointed Manmohan Singh to execute it.

Q) Another thing which you write in your book – the economist versus politician debate, that economists seem to have inflated opinions about themselves as agents of change whereas in reality it’s the political leadership which initiates change. Can you amplify?

A) You see many of the ideas, what happened in 1991 – almost every single initiative that was taken, including delicensing and decontrol, the devaluation of rupee, the reduction of fiscal deficit, trade policy reform – every single important policy decision that was taken were ideas economists have been writing about at least from the early 80s onward, many of them were within the government; they were writing reports for the government on what should be done, so it’s not as if the ideas suddenly came to the surface, ideas were all there but the political leadership in the 80s, particularly Rajiv Gandhi, were unable to implement these ideas. I make the point that Rajiv Gandhi had more than 400 MPs in Lok Sabha. He had a two-thirds majority and yet he did not have the political vision or political courage to implement the kind of radical policy changes Narasimha Rao initiated. Then came V.P. Singh — though he very much liked the ideas of change, he did not have the political imagination. I argue, therefore, that the crisis of 1991 was created by the inability of Rajiv Gandhi and V.P. Singh to undertake change; and it’s only when the crisis happened that Chandra Shekhar came under pressure and then the change process began

PV: The Accidental Prime Minister

Q) So in a sense it began from the Chandra Shekhar government onwards… Looking back, when we try to reconstruct a portrait of Narasimha Rao, he was also an accidental Prime Minister, one of the dark horses nobody thought that he would become the prime minister and yet he rose to the occasion and left a very enduring legacy. What were defining traits and qualities of Narasimha Rao that made him the kind of decisive leader he turned out to be? Did you know him personally?

Q) So in a sense it began from the Chandra Shekhar government onwards… Looking back, when we try to reconstruct a portrait of Narasimha Rao, he was also an accidental Prime Minister, one of the dark horses nobody thought that he would become the prime minister and yet he rose to the occasion and left a very enduring legacy. What were defining traits and qualities of Narasimha Rao that made him the kind of decisive leader he turned out to be? Did you know him personally?

A) I knew Narasimha Rao a little bit, my father knew him much better, but I would say that he understood how power works in Delhi, that keeping a low profile is the most important passport to political success in Delhi, and he kept a low profile…

But at the same time, he learnt on the job: he was Home Minister, Defence Minister, Education Minister and Foreign Minister; except for finance, he held all the other key portfolios, and in each of these jobs, he kept a low profile. Rajiv Gandhi and PM of the day Indira Gandhi got a lot of credit for a lot of work for what he did. In the process, he gained enormous experience. People don’t realize it, you should talk to foreign services officers who worked under him when he was the Foreign Minister; all of them tell me he was a fantastic learner, he knew what was happening in the world. He would read books, he would read articles, he was very well informed and all the diplomats who worked with him have said to me, those who are still alive and whom I have interviewed have said to me, he was a very good Foreign Minister, but then he allowed the prime minister of the day to take the credit for whatever work he did.

PV’s role in resetting India’s foreign policy

Q) Rao also initiated path-breaking changes in India’s foreign policy. For example, he launched Look East policy and started an outreach to Israel, leading to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. How do you look at defining foreign policy achievements of Rao?

A) My book is on 1991 – my book does not go into what happened after 1991. Look East was a little later….Just look at 1991, two key things happened that year. One is the collapse of the Soviet Union and his initial reaction was wrong because the Foreign Ministry told him that Gorbachev will not survive the coup, but he did survive the coup initially. Subsequently, many other changes came about and he understood the significance of that and reached out to the US on the one side and reached out to China on other side. The visit of China’s Premier in December 1991 was the starting point of the whole discussion on border. So with both the US and China, which are the two major powers in the post-Cold war, he took the initiative almost immediately. In my view that was the extremely important initiative on the foreign policy side.

Secondly, the first country he visited was Germany, he was quick to recognize the importance of Germany in Europe from India’s point of view. I think it was an extremely sagacious move because India needed technology, investment and market access and Germany was one of the countries with which India had good relations. Like Germany, India wanted to become a member of the UN Security Council. Therefore, to identify Germany as a country that he will first go to, when you look back, it was a very wise decision. Subsequently, in the case of Israel, the way he maneuvered Yasser Arafat when he was in Delhi and got him to virtually endorse India’s outreach to Israel, overturning a 40-year policy on Israel. In my view, the Israel outreach was also part of the America outreach, he understood that in the US, the Jewish lobby was very powerful and so by establishing diplomatic relations with Israel he was actually sending a message to the US. In so far as Look East policy is concerned, which Rao launched in 1992, he was also the first Indian PM to visit South Korea and South Korea became one of the major investors in India. Today South Korean brands are all over in India, and it all happened after 1991. In a sense, the entire post-cold war foreign policy of India was crafted by Narasimha Rao.

Q) But when you look back with hindsight it was quite amazing that the way Rao, for example, grasped the opportunities in Look East Policy, it wasn’t leveraged by his predecessor. I am talking about the Rajiv Gandhi era. Why were we so late in engaging with the economically vibrant region around us?

A) I think in the 80s, we were making very tentative moves. Indira Gandhi went and met Reagan. Rajiv Gandhi met Reagan and Rajiv Gandhi met Deng Xiaoping — all those first steps were taken; it’s not as if no steps were taken. But I think, by and large, our foreign policy establishment remained stuck in the Cold War framework, remained stuck in old foreign policy thinking; they were not realizing how the world was changing that we were entering a new rea and till we entered the new era there was no recognition that we are likely to be entering a new era….

There was not much recognition of the global power shifts taking place. There was some response though to power shifts… Indira Gandhi reached out Reagan, she was critical of the Soviet Union when they invaded Afghanistan, she told the Soviet Union very clearly that we are not in favour of what they had done in Afghanistan. She understood what was happening, but there was a lot of hesitation in being creative. In some ways, it was like what we have seen in this country in the last few years. We recognize that the world is changing once again with the rise of China, we recognise what needs to be done to deal with the rise of China, and yet we have been very hesitant. We tend to be extra cautious when it comes to international relations.

Q) Coming down to the present day, the Rao period brought out very starkly the organic linkage between the foreign policy and the international landscape and the politics of the day. Do you think the present government is able to mobilise political consensus to win support for its major foreign policy initiatives?

A) I think there is a huge difference between the way in which Narasimha Rao approached policy making and the way in which the present government is approaching. I think the present government takes its cue more from Indira Gandhi because the Prime Minister has a majority of its own, so he thinks he can do whatever he likes to do, like Indira Gandhi felt. Rao was running a minority government so he knew he could not do what he like; he had to reach out to the opposition. One of the most important relationships that helped him was his relationship with Atal Behari Vajpayee; both of them had excellent equations. In fact, Rao once requested Vajpayee to represent India at a UN conference, the two worked closely together, their thinking were very similar. They had very good personal equation, and I think Rao’s success was partly because he was able to keep the single largest opposition party on his side till December 1992. Till the Babri Masjid incident in December 1992, there was very little tension between him and the BJP. The Babri Masjid incident changed everything.

Bharat Ratna for Rao?

Q) The book is a very valuable corrective toward appraising Rao’s legacy, but there is still no official recognition. There is a long-standing demand that Rao should be conferred Bharat Ratna. Do you think there is a possibility that the Modi government will honour Rao?

A) Well, I certainly hope that they do. There is no reason why they should not. The only argument they can put forward is that you had 10 years of the Manmohan Singh government and he did not give him the Bharat Ratna. Manmohan Singh owed his career to Rao and yet Manmohan Singh was not able to give him Bharat Ratna. So Mr Modi can say that why should I give him?

On the other hand, I do think that the time has come to acknowledge Rao’s contribution to both Indian economic policy and foreign policy and to the rise of India in the 21st century — he laid the foundation for that rise. And the biography of Rao written by Vinay Sitapati has shown very clearly that he is the author of India’s nuclear weapons capability; he authorized the tests which Mr. Vajpayee finally conducted.

What prevented him to conduct nuclear tests at that point was that he felt the Indian economy economy was not yet to ready to withstand the impact of sanctions. Even Mr Vajpayee took two years after all; he first tried it in 1996 but finally the tests were conducted in 1998. By 1998, our foreign exchange reserves were quite high and the government felt that we could withstand the impact of sanctions.

Moving beyond Dynasty?

Q) In the political arena, Rao’s supreme achievement, many would say, was that he could prove that a non-dynastic politician could successfully run a Congress-led government, which was of course not palatable to the first family of the Congress. More than 25 years later, the Gandhi family seems to be perpetuating that myth that the Congress cannot go on without the Family? Do you see this party reinventing itself at all?

A) I can’t look into the future. Today it is a reality that the Congress has been drained of all leaders of stature, they are left with just Dr. Manmohan Singh and Rahul Gandhi; there is no other person in the Congress party who inspires respect in the rest of the country. But that was not the case 10 or 20 years back; there were still a large number of political leaders like Sharad Pawar, Mamata Banerjee, and Rajasekhara Reddy. There were a lot of political leaders who have either subsequently left the Congress or died, who could have emerged national leaders in Congress, but during the entire period of 1998 to 2008 the party decided that only Sonia can be the leader, they did not want any Indian Congress man of Indian origin as their leader. In that sense, the Congress had committed harakiri; my argument is that Rao had enormous regard for Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and even Sonia Gandhi. However, I think that he took the view that the Congress party is a national party; it is not a private party of any one family. Therefore, it should be revived as a national party and run as a national party, which means it will have a large number of regionally important leaders and it would have a Prime Minister who would have to be picked from time to time among those leaders. During Rao’s time, the Congress had Karunakaran, N.D Tiwari, Siddartha Shankar Ray, Arjun Singh, Sharad Pawar, Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy, Mamata Banerjee… So many leaders across the country were part of the Congress, but then the party decided that they did not want a non-Gandhi person.

A) I can’t look into the future. Today it is a reality that the Congress has been drained of all leaders of stature, they are left with just Dr. Manmohan Singh and Rahul Gandhi; there is no other person in the Congress party who inspires respect in the rest of the country. But that was not the case 10 or 20 years back; there were still a large number of political leaders like Sharad Pawar, Mamata Banerjee, and Rajasekhara Reddy. There were a lot of political leaders who have either subsequently left the Congress or died, who could have emerged national leaders in Congress, but during the entire period of 1998 to 2008 the party decided that only Sonia can be the leader, they did not want any Indian Congress man of Indian origin as their leader. In that sense, the Congress had committed harakiri; my argument is that Rao had enormous regard for Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and even Sonia Gandhi. However, I think that he took the view that the Congress party is a national party; it is not a private party of any one family. Therefore, it should be revived as a national party and run as a national party, which means it will have a large number of regionally important leaders and it would have a Prime Minister who would have to be picked from time to time among those leaders. During Rao’s time, the Congress had Karunakaran, N.D Tiwari, Siddartha Shankar Ray, Arjun Singh, Sharad Pawar, Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy, Mamata Banerjee… So many leaders across the country were part of the Congress, but then the party decided that they did not want a non-Gandhi person.

Modi needs second term for his legacy

Q) Your book seems to suggest that politicians were the heroes of 1991. Do you think at present time, politicians can be heroes or lead the country from the front?

A) First of all, at the national level now we have a popularly elected Prime Minister, we are back to the situation we were during Indira’s time, the Prime Minister with a popular mandate. I think between then and now we either had Prime Ministers who were accidental or who became Prime Minister as a result of coalition politics. Even Mr Vajpayee was the prime minister of a coalition. If the BJP had a majority in 1998, Advani may well have become the Prime Minister, but the reason Vajpayee became the Prime Minister was that he was the head of an NDA government, he was not the head of a BJP government — which means you have to have a person acceptable to other NDA parties. Similarly with Manmohan Singh, if the Congress had a majority in 2004 Sonia would have become the Prime Minister but because they didn’t have a majority, they needed somebody acceptable to the coalition partners; that is how Manmohan Singh became the Prime Minister. I think for the first time we have a Prime Minister who is popularly elected. Now, the entire political dynamic has changed. In the last few decades, we had accidental prime ministers. For the first time, we have a popularly elected prime minister.

Q) Towards the end of your book, you have written that democratic politics does not always offer an opportunity to a politician to become a statesman. With all the pulls and pressure of politics now, do you think Prime Minister Modi has an opportunity or is evolving as a statesman?

A) No, you have to win your second election to become a statesman. Manmohan’s Singh stature went up in 2009 because he won that election; it’s a different matter that the Congress party succeeded in finishing him off by 2014. But Modi’s image will finally depend on what happens in 2019. If he is a one-term prime minister, his legacy will be very different; if he is a two-term time Prime Minister, he will be seen as an icon. He needs another term to entrench his legacy.

Author Profile

- India Writes Network (www.indiawrites.org) is an emerging think tank and a media-publishing company focused on international affairs & the India Story. Centre for Global India Insights is the research arm of India Writes Network. To subscribe to India and the World, write to editor@indiawrites.org. A venture of TGII Media Private Limited, a leading media, publishing and consultancy company, IWN has carved a niche for balanced and exhaustive reporting and analysis of international affairs. Eminent personalities, politicians, diplomats, authors, strategy gurus and news-makers have contributed to India Writes Network, as also “India and the World,” a magazine focused on global affairs.

Latest entries

India and the WorldJune 26, 2025Operation Sindoor: India Sheds Restraint, Rediscovers Utility of Force

India and the WorldJune 26, 2025Operation Sindoor: India Sheds Restraint, Rediscovers Utility of Force India and the WorldJune 23, 2025BRICS summit in Rio to focus on Global South, local currency trade

India and the WorldJune 23, 2025BRICS summit in Rio to focus on Global South, local currency trade Africa InsightsJune 11, 2025New Opportunities in India-Japan Cooperation in Africa

Africa InsightsJune 11, 2025New Opportunities in India-Japan Cooperation in Africa India and the WorldMay 23, 2025Post-Operation Sindoor, India reminds Turkey, China of concerns and sensitivities

India and the WorldMay 23, 2025Post-Operation Sindoor, India reminds Turkey, China of concerns and sensitivities